When the State Becomes a Person: The Theft of a Nation’s Labour

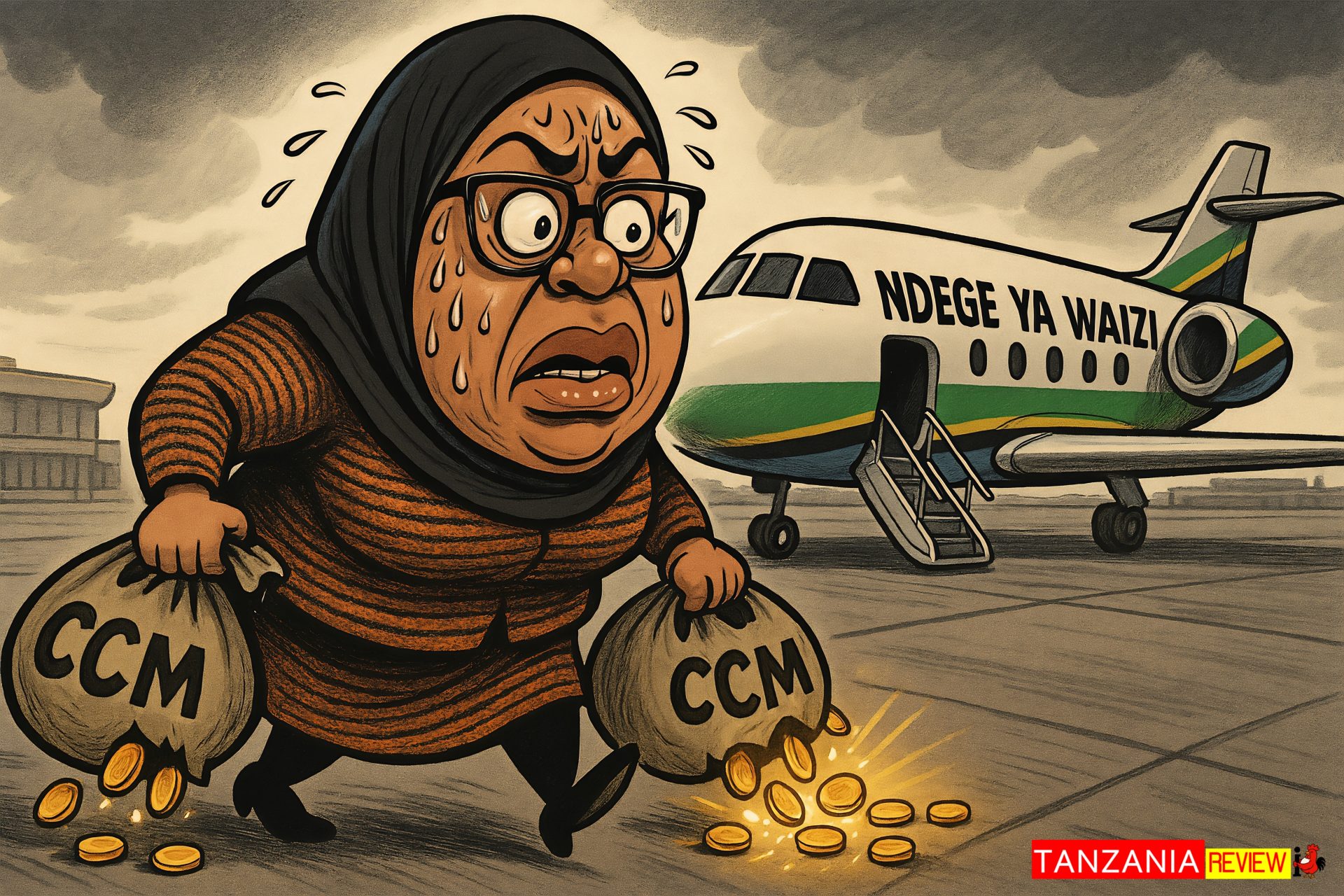

In Tanzania, a profound and unsettling shift is underway. Public assets, built and paid for by the collective taxes of its citizens, are being systematically rebranded. What was once understood as national infrastructure is now presented as a personal gift: ‘Samia’s roads’, ‘Samia’s electricity’, ‘Samia’s schools’. This strategic renaming is far more than a political vanity project; it is a calculated mechanism of control designed to erase the contributions of the people and foster a culture of dependency. This article delves into the deep-rooted corruption this narrative seeks to obscure, from the leaked bank statements of officials like IGP Wambura and the shadowy dealings of cronies like Abdul to the demoralisation of institutions like TISS.

Moving beyond mere critique, we explore a radical alternative grounded in Tanzanian realities and Swahili wisdom. We argue that the solution does not lie in seeking better leaders within a broken, pyramidal system, but in empowering communities from the bottom up. From Mbeya to Mwanza, and Tanga to Zanzibar, the true hope for Tanzania lies in reclaiming language, building networks of mutual aid, and forging a future based on voluntary solidarity—not state-sanctioned charity. This is a vision for a Tanzania built by and for its people, where power is distributed, not concentrated, and where sovereignty truly begins with the courageous words: “This is ours.”

The 20 Pillars of Power’s Playbook

The Silent Theft of Our Sweat: How They Make Us Forget What We Built

There is an old Swahili adage that says, “Mchumia juani, kibarua chini.” (He who works is in the sun, while the hired hand is in the shade). It speaks to a fundamental injustice: the disconnect between those whose labour creates value and those who ultimately claim the credit. Today, this adage finds a disturbing new life in the way our national achievements are presented to us. When a road, a school, or a water project—paid for by the collective sweat of millions of Tanzanians—is proudly unveiled as a personal gift from a leader, something profound is stolen from us. It is not just a misattribution; it is a surgical strike on our collective consciousness, designed to make us forget our own power.

This practice is perhaps the most potent tool of control. Let’s break down precisely how this mechanism works and why it is so deeply damaging to the spirit of a people.

1. The Alchemy of Transformation: From Our Wealth to Their Gift

First, consider the source. The concrete, the steel, the engineers’ designs, and the labourers’ toil—none of it materialises from thin air. It is funded by taxation. Every litre of petrol taxed, every VAT charge on a good purchased, every income tax deduction from a teacher’s or a driver’s salary: this is the pooled wealth of the nation. It is, in the truest sense, our money.

The act of renaming this infrastructure after a single individual performs a dark magic. It transforms what is a return on collective investment—something we have already paid for and rightfully own—into a bestowed favour from a benevolent ruler. We are placed in the position of grateful recipients, like children receiving a present, rather than empowered citizens enjoying the fruits of our own investment. This creates a culture of dependency, where we are taught to look upwards for provision, rather than inwards to our own capabilities and outwards to our communities.

2. Severing the Link Between Labour and Result

The psychological impact is profound. By erasing the collective contribution, the state severs the vital link between the people’s effort and the resulting progress. If a community struggles for years with a terrible road that hampers trade and access to healthcare, the final paving should be a moment of collective triumph—a testament to their enduring pressure, their taxes, and their right to development.

Calling it “Samia’s Road” rewrites this story. The struggle, the patience, and the financial contribution of the people are erased from the narrative. The leader becomes the sole author of the community’s fortune. This teaches a lesson of passive waiting rather than active claiming. It whispers that progress is not something you build, but something you are given—and that it can be taken away if you are not sufficiently grateful or compliant.

3. The Tanzanian Context: A Betrayal of Ujamaa and Self-Reliance

This is particularly jarring in Tanzania, a nation whose foundational philosophy, Ujamaa, was built upon the principles of familyhood, collective labour (kazi ya vikundi), and self-reliance. The vision, though imperfectly executed, was to create a society where people recognised their shared stake in building the nation together. The current trend of personalising state assets is a complete betrayal of that spirit. It replaces Ujamaa with a system that feels more like a modern-day feudalism, where a central court dispenses gifts to its subjects.

When even the most basic functions of the state—the police, the army, the judiciary—are framed as extensions of a person’s will (“Samia’s Police”), it fundamentally corrupts their purpose. It suggests they owe their allegiance not to the people or the constitution, but to the ruler. This justifies the brutal suppression of dissent, as seen when citizens dare to question this very narrative, because the protectors become the personal guards of the powerful, not the servants of the public.

When even the most basic functions of the state—the police, the army, the judiciary—are framed as extensions of a person’s will (“Samia’s Police”), it fundamentally corrupts their purpose. It suggests they owe their allegiance not to the people or the constitution, but to the ruler. This justifies the brutal suppression of dissent, as seen when citizens dare to question this very narrative, because the protectors become the personal guards of the powerful, not the servants of the public.A Radical Reclamation: Remembering Our Power

So, what is the alternative? It does not lie in simply voting for a more humble leader who will not put their name on things. The problem is not the personality, but the structure of power itself that allows for such appropriation.

The true resistance begins in the mind. It starts when we, the people, relentlessly correct the narrative. It is not “Samia’s electricity”; it is the electricity we paid for. It is not “her road”; it is the road our taxes built. This is not mere semantics; it is an act of intellectual reclaiming.

The ultimate answer lies in building power from the bottom up. It is found in communities that organise themselves to solve their own problems—through cooperative businesses, community-owned water management, and neighbourhood assemblies—demonstrating that we do not need a central authority to gift us what is already ours. It is about creating a society where, as the adage implies, those who work in the sun finally step out of the shade of the overseer and claim the harvest of their own labour. The goal is not to get a better master, but to become masters of our own lives and our shared destiny.

The Great Father Myth: How We Are Made Children in Our Own Land

There is timeless wisdom in the Swahili saying, “Mkono mmoja haulei mtoto.” (One hand cannot raise a child). It speaks to a profound truth: that nurturing, growth, and achievement are fundamentally collective endeavours. No single person, no matter how powerful, can claim sole credit for the well-being of a whole community. Yet, across Tanzania, a dangerous and infantilising story is being sold to us. It is the story of the Great Father, the benevolent leader who single-handedly provides for the nation. When every new road, school, or power grid is presented not as our collective achievement but as a personal gift from a leader, we are not being honoured—we are being diminished. This is the careful cultivation of a cult of the individual, a strategy designed to keep a population passive, grateful, and permanently in a state of childhood.

1. The Psychology of the Gift-Giver

At its core, this strategy is about power disguised as generosity. A gift, by its very nature, creates an obligation. It puts the receiver in a position of debt and gratitude towards the giver. When the state, funded by our own taxes and labour, turns public infrastructure into “personal gifts” from a leader, it inverts the natural order of responsibility.

We are transformed from rightful owners into indebted recipients. Our role shifts from active citizens who demand what is ours to passive children who must say “thank you” for what we are given. This fosters a paternalistic relationship where the government is the all-knowing parent (the Mzazi) and the people are the children (watoto) who must be obedient and trusting. This dynamic kills the very spirit of critical inquiry and self-determination that a healthy society requires. We are taught to wait for instructions, not to initiate actions; to accept what we are given, not to demand what we deserve.

2. The Betrayal of Ubuntu and Ujamaa

This cult of the individual is a direct affront to the deepest currents of Tanzanian and African philosophy. Concepts like Ubuntu (“I am because we are”) and Ujamaa (familyhood) are rooted in the irreducible truth that our humanity and our progress are interdependent. They assert that community is built by many hands and that leadership is a temporary role of service within the community, not a position of ownership over it.

To place one person’s name on everything that the multitude has built is to spit in the face of this wisdom. It replaces the circle of community with a pyramid of power. It says, “Forget the ‘we.’ Honour the ‘I’.” This is a profound cultural and spiritual betrayal, replacing a worldview of shared responsibility with one of top-down authority. It is a foreign import of the worst kind, dressed in national colours.

3. The Erosion of Collective Confidence

The most damaging long-term effect of this “Great Father” myth is the erosion of our belief in our own power. When a society is constantly told that all good things come from a single, central source, it begins to doubt its own ability to organise, build, and solve problems without that source.

Community-led initiatives wither because people start to believe that only the government can undertake large projects. Mutual aid networks—the traditional bedrock of African resilience—are weakened because we are coached to look to the state for salvation. This creates a vicious cycle: the more we are disempowered, the more we need to be “saved,” which further strengthens the power of the saviour. It is a strategy designed to make us helpless so that we will accept control.

Reclaiming Our Adulthood: From Gratitude to Demand

The resistance to this begins with a simple, radical act of mental refusal: we must stop saying “thank you” for what is already ours.

The alternative is not to find a more generous leader. It is to dismantle the very idea that we need a Great Father to begin with. It is to remember that real power—the power to build, to care for one another, and to manage our affairs—has always resided in our communities, in our unions, in our neighbourhood assemblies, and in our willingness to cooperate directly, without a master orchestrating our lives.

It is about building a society where, as the adage teaches, the many hands that raise the child—that build the road, maintain the water source, and keep the peace—are the same hands that hold the power. We must move from a culture of grateful children to one of empowered adults, capable of governing ourselves. For a nation, that can rule itself from the bottom up has no need for a father to rule it from the top down.

The Great Deception: Unmasking the “Gift” That Was Already Ours

A wise Swahili proverb teaches us, “Mto huishi na mkizi, lakini haushi na mwenyeji.” (A river can do without a crocodile, but it cannot do without the local community). This speaks to a fundamental truth: the source of life and sustenance is the collective—the water, the land, and the people who tend to it. The crocodile, a powerful but external force, is an optional addition, often a predator. In modern Tanzania, a similar deception is at play. The government, funded by the people, presents the basic infrastructure of life—water, electricity, schools—as personal gifts from a benevolent leader. This is not benevolence; it is a grand illusion designed to obscure a simple fact: we are not receiving gifts, we are finally receiving a minuscule return on our collective investment, and we should be demanding more, not thanking for crumbs.

1. The Arithmetic of Theft: Understanding the “Social Contract”

The concept is simple, though those in power work tirelessly to complicate it. The state is not a wealthy patriarch with a bottomless purse. Every shilling in its coffers comes from us. It is collected through taxes on our incomes, VAT on the goods we buy, levies on the businesses we run, and tariffs on the resources extracted from our land. This collective pool of wealth is meant to be managed and redistributed for the common good—a return on our social investment.

Therefore, a new school is not a “gift.” It is a dividend. A new water pipeline is not a “donation.” It is a basic return on investment. To frame it as the former is a form of financial gaslighting. It is like a bank manager taking your savings, using them to build a house, and then presenting the keys to you as an act of his personal charity, expecting your grovelling gratitude while he still controls the deed. This illusion masks the reality of the transaction: they are using our money to build what we need, and then demanding our thanks for the privilege.

2. The Manufacture of False Gratitude

This deliberate mis-framing is a potent political tool. Gratitude is a powerful emotion that disarms critique and fosters loyalty. By manufacturing a false sense of gratitude, the state seeks to replace our critical citizenship with obedient follower-ship.

When a community that has paid taxes for decades finally gets a connected electrical grid, the moment should be one of righteous expectation met, not miraculous salvation received. The language of “gifts” corrupts this. It teaches people to be grateful for what they should rightfully expect, lowering the bar for what is considered acceptable governance. It shifts the conversation from “Is this service adequate and well-maintained?” to “Aren’t we lucky to have been given this at all?” This is how a population is trained to settle for less, to accept mediocrity, and to see the fulfilment of basic rights as an extraordinary favour.

3. The Tanzanian Reality: From Ujamaa to Paternalism

This illusion is a bitter pill for a nation founded on the principles of Ujamaa and self-reliance. Ujamaa was, in its essence, about collective ownership and communal effort. It was about villages pulling together to build their futures. The modern “gift-giving” state is the antithesis of this. It has replaced horizontal community-building with vertical, top-down patronage. It has twisted the concept of kujitegemea (self-reliance) into a cruel joke, where we are to be self-reliant individuals who are simultaneously utterly reliant on the benevolence of the state for everything.

This system creates a perverse dependency. It discourages communities from organising their own solutions because they are taught to wait for the “gift” from the capital. It kills local initiative and reinforces the power of a centralised authority that doles out development as a reward for political compliance.

Reclaiming the Narrative: From Gratitude to Rightful Claim

The radical response to this illusion is to shatter it with clear, uncompromising language.

We must never say, “The government gave us a school.”

We must always say, “Our taxes finally built that school.”We must correct our neighbours, our friends, and our families. We must reframe every “gift” as a “delayed return.” This is not semantics; it is a foundational act of political resistance. It is a reclaiming of ownership and agency.

True power lies not in waiting for a benevolent master to provide, but in building the world we want ourselves, through co-operatives, community-owned utilities, and mutual aid networks that answer to us, not to politicians. The river of our collective wealth can and must flow for the benefit of the community that sustains it, without the crocodile claiming credit for the water. Our gratitude should be reserved for each other—for our shared labour and patience—not for those who merely manage the vault where our collective wealth is stored.

True power lies not in waiting for a benevolent master to provide, but in building the world we want ourselves, through co-operatives, community-owned utilities, and mutual aid networks that answer to us, not to politicians. The river of our collective wealth can and must flow for the benefit of the community that sustains it, without the crocodile claiming credit for the water. Our gratitude should be reserved for each other—for our shared labour and patience—not for those who merely manage the vault where our collective wealth is stored.The Hijacking of the Shield: When Protection Becomes Possession

There is a profound Swahili adage that warns, “Mlinzi aliyenunuliwa kwa fedha, atauza mlinzowe kwa fedha.” (A guard who was bought with money, will sell his ward for money). This speaks to a universal truth about loyalty: when a protector’s allegiance is pledged not to principle or community, but to a purse, their protection becomes a commodity, not a covenant. In Tanzania today, we witness a dangerous perversion of this very idea. The systematic rebranding of core national institutions—the police, the army, the judiciary—by prefixing them with a leader’s name is not an honour. It is a public weaponisation of symbols, a deliberate and sinister strategy to transform institutions meant to serve the public into a private guard loyal to the regime. It signals a fundamental shift from service to sovereignty, where the populace are no longer the masters to be protected, but the subjects to be policed.

1. The Corruption of Purpose: From Public Service to Personal Duty

The police force and the national army are, in their truest sense, meant to be servants of the public good. Their legitimacy is derived from their mandate to protect the people, their rights, and their property. Their allegiance should be to the constitution and the rule of law—impersonal principles designed to apply equally to all.

Attaching a leader’s name—“Samia’s Police”—shatters this impersonal covenant. It reorients the entire institution’s sense of duty. Their mission is no longer “to serve and protect the public” but to “serve and protect the regime.” Their loyalty is redirected from an abstract concept of justice to the very concrete person sitting in State House. This explains why these forces can so easily turn their weapons on the very citizens they are sworn to protect during protests. In their minds, they are not brutalising the public; they are defending their patron from dissent. They are following orders, not upholding law.

2. The Psychological Signal to the Populace

This renaming is a powerful psychological tool aimed at both the institution and the society it controls. For the ordinary citizen, the message is clear and threatening: “These forces do not belong to you. They belong to her. They answer to her. Your safety is contingent upon your obedience to her.” It manufactures a climate of fear and subservience, teaching people that authority is personal and absolute, not democratic and accountable.

For the officers and soldiers within these institutions, the constant repetition of the phrase is a form of ideological conditioning. It reinforces a chain of command that leads directly to an individual, not to the nation. It demoralises those who joined with a genuine desire to serve their country, as they are forced to become enforcers for a political clique, while simultaneously emboldening those whose ambitions are for power and patronage, seeing the institution as a vehicle for personal gain.

3. The Betrayal of National Unity and Ujamaa

This act is the ultimate betrayal of the Tanzanian spirit of Ujamaa—familyhood. A family’s security is collective; a father does not own the children’s protectors. By claiming ownership of these institutions, the leadership places itself above the national family, as a feudal lord over serfs. It dismantles the idea of shared national identity and replaces it with a hierarchy of loyalty where the leader is the sun, and all other institutions, and indeed citizens, must orbit around her.

It creates a nation within a nation: a small, armed, and loyal elite tasked with controlling the disarmed, dependent majority. This is not unity; it is domination dressed in national colours.

Reclaiming Our Guardians: The Power of Refusal

The resistance to this weaponisation must be as symbolic and steadfast as the act itself. It begins with a conscious and collective refusal to use the corrupted language.

We must never say “Samia’s Police.”

We must say “the police force” or “our police,” emphasising their public ownership.We must relentlessly point out the truth: that their salaries are paid by our taxes, their uniforms stitched by our labour, and their mandate derived from our collective right to security. We must remind them and ourselves that they are public servants, not private militias.

Ultimately, true security cannot be outsourced to a centralised force that pledges allegiance to a person. The only durable, ethical form of security is one built from the ground up—through community-based peacekeeping, neighbourhood watches, and systems of accountability where protectors are directly answerable to the communities they serve, not to a distant ruler. We must strive for a society where our guardians are of us, for us, and by us, their loyalty earned through service, never purchased by power. For a guard who serves the community will never sell it.

The Cage of Care: How We Are Taught to Be Helpless

There is a piercing wisdom in the Swahili adage, “Mkono mtupu haulambwi.” (An empty hand is not licked). It speaks to a stark reality: initiative and self-reliance are necessities of life. Yet, in Tanzania today, a more insidious lesson is being taught from on high. It is a lesson of calculated dependency. From the airtime on our phones to the awards given to our artists, the state is weaving a web of narrative that insists every facet of our existence is a benefaction from its hand. This is not development; it is a sophisticated strategy to create a nation of dependents, to stifle the innate human capacity for self-organisation, and to ensure that power remains forever centralised, because a people who cannot imagine providing for themselves will never dare to govern themselves.

1. The Architecture of Dependency: From Necessity to Luxury

The strategy is diabolical in its completeness. It moves far beyond roads and electricity, infiltrating the very fabric of social and cultural life.

Communication: When the government brands subsidised mobile data or airtime as a “gift,” it reframes a modern necessity—the very tool of organisation and information—as a luxury bestowed by a generous patron. It creates a subconscious link: your ability to connect with your family or run your business is tied to the state’s goodwill.

Culture: When music awards or artistic grants are personally branded by the leader, it sends a clear message to creators: your recognition and livelihood are not earned by your talent and the people’s appreciation, but are granted by the regime. This subtly encourages self-censorship and art that flatters power, corroding culture’s role as a mirror to society.

Basic Sustenance: The pattern repeats with agricultural inputs, microloans, and disaster relief. These are presented not as our collective wealth being returned to us in time of need, but as the personal charity of the ruler. This transforms a right into a favour, making people queue up as supplicants rather than stand tall as citizens.

2. The Erosion of Community Muscle

This manufactured dependency has a devastating effect on our communal spirit. The pervasive message that “the state will provide” actively discourages people from solving their own problems collectively. It teaches helplessness.

Why would a community pool its resources to fix a local water pipe if it is taught to wait for the government to do it? Why would artists form a co-operative to fund their work if they believe success can only come via state recognition? This system systematically atrophies the “muscle” of mutual aid and community initiative that has been the bedrock of African societies for millennia. It replaces the horizontal bonds of ujamaa (familyhood) with vertical chains of patronage.

3. The Political Pay-Off: A Nation of Supplicants

For the powerful, this widespread dependency is the ultimate insurance policy. A population that relies on the state for everything—from its entertainment to its entrepreneurship—is a population that is far easier to control.

It kills dissent: How can you bite the hand that you are told feeds you? Criticism becomes framed as ungratefulness, a sin against the provider.

It ensures compliance: The threat is never spoken but always implied: step out of line, and the “gifts” may stop. Your business licence, your grant, your recognition could vanish.

It creates a passive citizenry: People who are trained to wait for solutions will not actively organise to create their own. They become political spectators, not participants.

Reclaiming Our Capacity: Licking Our Own Hands

The radical defiance to this strategy is to actively, visibly, and joyfully rebuild our self-reliance. It is to prove the adage true by ensuring our hands are never empty.

It is about creating what we need, ourselves. It is artists organising independent festivals funded by their communities. It is villages forming collectives to harvest rainwater or install solar micro-grids. It is workers forming unions and co-operatives that answer to them alone. It is using our own resources, our own ingenuity, and our own labour to meet our needs, without permission or patronage.

It is a conscious rejection of the beggar mentality. We must look at the so-called “gifts” and say: “This is not a donation. This is a delayed and inadequate return on the wealth you have extracted from us. We can and will do better for ourselves.”

True freedom is not about receiving better gifts from a kinder master. It is about smashing the cage of care altogether and rediscovering the powerful truth that we, the people, organised in our communities, are the only true source of our own sustenance, our own culture, and our own power. Our hands, when working together, are never truly empty.

The Currency of Complicity: How Silence is Purchased and Power is Protected

There is a chilling Swahili adage that reveals a timeless truth about power and corruption: “Akili za mvua ni za kufujisha, akili za mpepo ni za kuvunjavunja.” (The wisdom of the rain is to soak, the wisdom of the wind is to break). The wisdom of the corrupt, however, is neither to nourish nor to destroy openly, but to infiltrate, to purchase, and to silence. The leaked bank statement of IGP Wambura was not merely a financial document; it was a window into this dark wisdom. It revealed a simple, brutal transaction: staggering sums of money, flowing from figures like Abdul, buying the most valuable commodity in the nation—the silence of those sworn to protect it. This is how a system functions, not by winning hearts and minds, but by purchasing the souls of those who could dismantle it.

1. The Economics of Betrayal: From Public Servant to Private Mercenary

The transformation of a high-ranking official into a billionaire overnight is not a success story; it is a story of profound betrayal. It represents a fundamental perversion of their role.

These individuals are not paid a salary for their personal enrichment. They are granted authority and a wage in trust, for the execution of a public duty. Their position is meant to be a vessel for service. When that vessel is filled with illicit millions from shadowy benefactors, the original purpose is evicted. The official’s loyalty is surgically transferred from the public to the patron. Their continued wealth, status, and power are no longer tied to their performance in serving the people, but to their performance in serving the interests of the corrupt network that owns them. They become mercenaries, guarding the vault of a kleptocracy, not servants guarding the well-being of a nation.

2. The Anatomy of the Silence

This purchased loyalty manufactures a silence that is deafening. It is not a passive quiet, but an active, enforced void.

Silence from Enforcement: How can the IGP investigate corruption he is financially entwined with? His silence is not mere inaction; it is a protective barrier around himself and his benefactors. It ensures that the police force, the institution meant to uphold law, becomes the primary instrument for protecting lawbreakers.

Silence from the Judiciary: When judges and magistrates are woven into the same web of patronage, the courts become theatres of injustice, where the powerful are immune, and the whistle-blowers are persecuted. Their silence is the gavel that never falls on the guilty.

Silence from the Bureaucracy: Technocrats and administrators see the corruption and understand the mechanics of the theft. But their silence is bought through smaller bribes, threats, or the promise of promotion. They learn to look away, to falsify documents, to approve fraudulent deals.

This collective, purchased silence creates a culture of impunity so thick it becomes the very air the system breathes. It normalises the abnormal.

3. The Moral Bankruptcy and the Erosion of Trust

The most devastating casualty of this complicity is the total erosion of public trust. When those in uniform and those in robes are revealed to be billionaires while ordinary citizens struggle, the social contract is not broken—it is revealed to have been a lie all along.

People no longer see a public servant; they see a gangster in a uniform. They do not see a justice system; they see a protection racket. This breeds a deep, nihilistic cynicism that is toxic to any society. It teaches the bitter lesson that integrity is for fools, and that the only way to succeed is to become part of the corruption or to accept it helplessly. It demoralises every honest officer, every dedicated civil servant, making them feel like a sucker for playing by the rules.

Breaking the Silence: The Radical Act of Speaking Truth

In a system where silence is the currency of power, the most radical act is to speak. To name names. To follow the money. To reject the lie that this is just “how things are.”

The alternative to this complicity is not finding more honest leaders to put at the top of the same rotten system. The alternative is to stop looking for saviours at the top altogether.

It is to build counter-systems of accountability from the ground up. It is communities creating their own independent oversight committees to monitor local projects. It is journalists and activists forming solidaristic networks to protect each other. It is workers’ unions refusing to be bribed and instead demanding transparency.

It is about making corruption too dangerous to practice, not by appealing to a corrupt central authority, but by creating our own power. We must become the un-bribable, the un-silenceable. We must remember that while the wisdom of the corrupt is to purchase silence, the wisdom of the people, like the relentless rain, must be to soak through every lie, and like the persistent wind, to break down every wall of complicity, until nothing is left hidden. For a truth spoken aloud is the first crack in the foundation of a corrupt empire.

The Engine of Control: How Deliberate Corruption Holds a Nation Hostage

There is a stark Swahili adage that lays bare the mechanics of power: “Mwenye makucha ndiye mwenye nema.” (He who has claws is the one who has bounty). In its rawest form, it speaks not to fair reward for hard work, but to the reality that power and wealth are often taken and held by force and cunning, not granted by merit. In Tanzania, this adage finds its most sinister expression in a truth many feel but few dare to articulate: the overwhelming corruption is not a sign of a broken system. It is the system’s primary engine. It is not a flaw to be corrected; it is the meticulously designed feature that ensures the entire structure of control remains standing. It functions as the glue binding a network of elites to the status quo, giving them everything to lose should the people ever truly awaken.

1. The Network of Complicity: Building a Pyramid of Mutual Blackmail

Systemic corruption does not create lone wolves; it creates a pack. The leaked billions in an official’s account, the lucrative contracts handed to cronies like Abdul, the silent partnerships in sprawling business ventures—these are not isolated acts of greed. They are the deliberate construction of a network.

Each illicit transaction is a thread weaving a web of mutual complicity. The businessman compromises the police chief. The police chief compromises the politician. The politician compromises the judge. This creates a pyramid of mutual blackmail, where every elite player is both a blackmailer and a victim. Their collective guilt becomes their collective security. To expose another is to expose oneself. Therefore, their shared, vested interest is not in good governance, but in the absolute preservation of the system that protects their secret and sustains their wealth. Their loyalty is not to an idea or a nation, but to the preservation of the corrupt network itself.

Each illicit transaction is a thread weaving a web of mutual complicity. The businessman compromises the police chief. The police chief compromises the politician. The politician compromises the judge. This creates a pyramid of mutual blackmail, where every elite player is both a blackmailer and a victim. Their collective guilt becomes their collective security. To expose another is to expose oneself. Therefore, their shared, vested interest is not in good governance, but in the absolute preservation of the system that protects their secret and sustains their wealth. Their loyalty is not to an idea or a nation, but to the preservation of the corrupt network itself.2. The Vested Interest in Violence and Suppression

This is where corruption transforms from theft into a mechanism of brutal control. When your entire fortune and freedom are predicated on a corrupt system, any threat to that system becomes an existential threat to you.

This is why dissent is not merely disagreed with; it is crushed with overwhelming and often violent force. A protest against rising fuel prices is not seen as a civic grievance; it is seen as a direct attack on the fuel importation contracts that line the pockets of the powerful. A demand for transparency in the mining sector is not a call for accountability; it is a threat to the secretive deals that create billionaires overnight. The elite’s claws—the police, the judiciary, the intelligence services—are unleashed not to protect the public, but to protect the bounty. Their violence is a rational, calculated response to protect their illicit wealth. It is the cost of doing business.

3. The Illusion of Reform and the Cycle of Dependency

The genius of this control mechanism is that it also manufactures its own justification for existence. By hollowing out public services through theft, the state creates poverty and desperation. It then presents itself as the sole provider of solutions, albeit inadequate ones, creating a crippling cycle of dependency.

The system offers the occasional, highly publicised anti-corruption prosecution—a sacrificial lamb to maintain the illusion of justice and reform. But this is merely theatre. It convinces the public that the problem is being handled, that the “bad apples” are being removed, all while the root of the tree remains utterly rotten and the core network remains untouched. This illusion is a pressure valve, releasing public anger without ever addressing the source of the heat.

Reclaiming Our Wealth: Dissolving the Network of Control

The radical response to this engineered corruption is to recognise that it cannot be reformed from within. A system built on corruption will always produce corrupt outcomes. Appealing to the conscience of the clawed is a futile endeavour.

The true path lies in dissolving their power by building our own. It means:

Building Economic Autonomy: Creating community-owned co-operatives for agriculture, energy, and credit that operate transparently and answer to members, not patrons. This drains the swamp of dependency that corruption feeds on.

Creating Parallel Systems of Accountability: Forming independent citizen audit committees to monitor local government expenditure and project implementation, using grassroots power to demand transparency where formal institutions have failed.

Solidarity, Not Patronage: Replacing the vertical relationship of supplicant-and-patron with horizontal networks of mutual aid between communities, trade unions, and activist groups. When we provide for each other, we break the cycle of dependence that makes us vulnerable to corruption’s empty promises.

The bounty of Tanzania does not belong to those with the claws to steal it. It belongs to the people whose labour creates it. The goal is not to clip the claws of the powerful one by one, but to build a society where such claws are rendered useless—a society based on mutual respect and shared prosperity, where power is so diffuse and local that it cannot be bought or sold. For the ultimate defence against a system built on corruption is to stop needing it altogether.

The Guard Dog That Preys on Its Owners: The Logic of a Police State

A piercing Swahili adage asks a simple, devastating question: “Mbwa mmekufa nani?” (The dog has died of what?). It is a call to examine the root cause of a failure. When a guard dog meant to protect the homestead instead turns on the livestock it was meant to guard, the question is not about the dog, but about the master who trained it. In Tanzania, we are witnessing this very tragedy. The police force, an institution meant to serve and protect the community, has been transformed into a private security detail for a corrupt political and economic elite. Their infamous brutality against dissent is not a sign of overzealousness; it is the cold, logical behaviour of a guard dog whose loyalty has been purchased. It has no moral ground because it serves interests, not justice; it protects a pipeline of patronage, not a populace.

1. The Perversion of the Shield into a Sword

The fundamental role of the police in any society should be to uphold a common law that protects the safety and rights of all. Their legitimacy is derived from their service to the public good. However, when their allegiance is redirected from the community to a corrupt leader—when they become “Samia’s Police” in spirit and action—their entire purpose is inverted.

The shield of public service is reforged into a sword for regime protection. Their violence is not a breakdown of order; it is the enforcement of a new, sinister order. This order prioritises the uninterrupted flow of illicit wealth to the powerful over the safety and rights of the people. A protest is not a civic engagement to be managed; it is a threat to the cash flow of their ultimate patrons. Therefore, crushing it with extreme prejudice is not an error in judgement—it is the successful execution of their primary, albeit unstated, mission.

The shield of public service is reforged into a sword for regime protection. Their violence is not a breakdown of order; it is the enforcement of a new, sinister order. This order prioritises the uninterrupted flow of illicit wealth to the powerful over the safety and rights of the people. A protest is not a civic engagement to be managed; it is a threat to the cash flow of their ultimate patrons. Therefore, crushing it with extreme prejudice is not an error in judgement—it is the successful execution of their primary, albeit unstated, mission.2. The Economics of Brutality

The leaked bank statements of officials like IGP Wambura are not just evidence of corruption; they are the key to understanding this brutality. They reveal that top brass are not salaried civil servants, but billionaire beneficiaries of a kleptocratic network involving figures like Abdul.

This purchased loyalty trickles down. Promotions, bonuses, special allowances, and protection from prosecution are the currencies used to buy the compliance of the rank and file. An officer who might personally hesitate to beat a peaceful protester is compelled by a system that rewards cruelty and punishes compassion. Their own livelihood becomes tied to the perpetuation of the corrupt system. Thus, the boot that meets a protester’s ribs is not just enforcing state power; it is protecting the officer’s own stake in a lucrative, illicit economy. It is personal.

3. The Betrayal of Ujamaa and the Community

This model of policing is the absolute antithesis of the Tanzanian ideal of Ujamaa—familyhood. A family’s security is collective and mutual. What we have instead is a feudal model, where an armed elite is tasked with controlling the disarmed population on behalf of the lord of the manor. The police are no longer part of the community; they are an occupying force that lives among it, their interests alien to those they patrol.

This explains the deep-seated fear and resentment many communities feel. They do not see protectors; they see enforcers. They see the very individuals who allow drug rings or corruption to flourish in their neighbourhoods (if the price is right) suddenly become brutally efficient when students march for justice. The inconsistency reveals the truth: their mandate is not safety, but control.

Reclaiming Our Security: From Enforcers to Community

The solution is not to plead for a gentler police force. A guard dog trained to attack cannot be asked to be nicer; it must be retrained from the ground up, or replaced entirely.

The radical alternative is to begin the work of reclaiming our own security. This means:

Withdrawing Consent: Actively refusing the legitimacy of a force that serves power instead of people. Documenting their abuses, supporting victims, and creating a public consensus that they are not our protectors.

Building Community Defence: Reviving and formalising community-based protection systems. This could involve neighbourhood watches, community peacekeeping teams, and restorative justice circles that handle conflict without state intervention. These groups are accountable to the community they come from, not to a distant, corrupt capital.

Solidarity, Not Subjugation: Creating strong networks of mutual aid so that communities are resilient and less dependent on a state that only offers violence in return. When we care for each other, we become less vulnerable to the threats of those in power.

The adage forces us to ask: “The dog has died of what?” The dog has died of a poisoned master. It has died of loyalty bought and sold. The answer is not to mourn the dog, but to build a new form of security where the community guards itself, for itself, with accountability and shared interest as its only guiding principles. True safety cannot be outsourced to those whose interests lie in our oppression.

The Broken Compass: When Patriotic Spirit is Crushed by Corruption

There is a profound Swahili adage that speaks to the core of integrity: “Ukweli haubaki mfichama.” (The truth does not remain hidden). Yet, within the halls of power, a different, more sinister reality is enforced. For the patriotic individual working within a state institution like the Tanzania Intelligence and Security Services (TISS), this adage becomes a source of profound torment. They are the ones who see the truth that is meant to remain hidden—the rot, the corruption, the blatant betrayal of the nation’s ideals. This is not a simple case of workplace dissatisfaction; it is a systematic demoralisation, a deliberate breaking of the human spirit. It is the process by which patriots are forced to become either silent accomplices or ostracised targets, ensuring the corrupt machine operates without internal challenge.

1. The Agony of the Patriotic Insider

Imagine the position of a dedicated, well-trained TISS officer. They likely joined the service with a genuine desire to protect their nation, to serve the people, and to uphold the law. They are the ones with the clearest view of the grotesque gap between the institution’s stated mission and its actual operation.

They see the leaked bank statements of their superiors. They witness the illicit meetings with shadowy figures like Abdul. They are ordered to investigate and silence citizens who are protesting the very corruption they are forced to facilitate. For a person of conscience, this creates a unbearable cognitive dissonance. Their professional duty, which should align with their patriotic values, now directly contradicts them. They are ordered to protect the very thing that is harming their country. This is psychological violence that erodes their spirit far more effectively than any external enemy could.

2. The Two Prisons: Complicity or Isolation

The system offers these individuals a brutal choice with no true escape, only different forms of confinement.

The Prison of Silent Complicity: This is the path most are forced to take. To keep their job, to provide for their family, and to avoid becoming a target themselves, they must swallow their principles. They look the other way, they file false reports, they follow unlawful orders. Each day, they die a small moral death. This silent majority within compromised institutions is the bedrock of the status quo. Their inaction is not approval; it is a form of coercion, a survival mechanism in a toxic environment. Their morale isn’t just low; it is necrotic.

The Prison of Isolation: For the few who cannot stomach the compromise and dare to speak up or resist, the punishment is swift and absolute. They are not just fired; they are isolated, smeared, labelled as traitors or unstable, and often threatened. Their careers are destroyed, and their professional networks vanish. They are made an example of to ensure others remain compliant. This option is so terrifying that it makes the prison of silence seem like the only rational choice.

3. The Strategic Outcome for Power

This demoralisation is not an accidental byproduct; it is a strategic victory for the corrupt core. A demoralised institution is a pliable one.

By systematically removing or silencing individuals of integrity, the leadership ensures that the entire apparatus is staffed by either the willingly corrupt or the neutrally compliant. It creates a culture where ethical behaviour is a liability and obedience is the only currency. This ensures that the intelligence service focuses its power not on external threats to the nation, but on internal threats to the regime—namely, its own citizens and the few honest souls within its ranks who might still dare to whisper the truth.

Reclaiming Integrity: From Institutional Loyalty to Moral Duty

The radical response to this demoralisation is a profound shift in loyalty—from the institution to one’s own conscience and to the people.

The true patriots are not those who blindly follow orders from a corrupt chain of command. The true patriots are those who recognise that the highest duty is to the truth and to the well-being of their fellow citizens. This can take many forms:

Conscientious Objection: Refusing to carry out orders that are blatantly unlawful or immoral, regardless of the personal cost.

Anonymous Revelation: Becoming a source of truth for independent journalists and activists, carefully leaking information that exposes the rot, thus serving the public instead of the powerful.

Building Solidarity Networks: Connecting with other demoralised individuals within the system to create a covert community of conscience, offering mutual support and protection.

The goal is to realise that the institution does not hold a monopoly on patriotism. In fact, when the institution becomes the enemy of the people, true patriotism means resisting it. We must celebrate those who break their silence, who risk everything to align their actions with their values. For it is only when the truth, however hidden, is brought into the light by acts of immense courage that the foundations of a corrupt system begin to crack. The ultimate demoralisation is not within the hearts of the honest, but in the crumbling facade of a power structure that has betrayed its very reason for existing.

The Patronage Parasite: Unmasking the So-Called ‘Benefactors’

There is a timeless Swahili adage that cuts to the heart of this deception: “Mkulima hmfanyi biashara na mwenye shamba.” (A farmer does not do business with the owner of the farm). The saying reveals a fundamental power imbalance: one party owns the land and sets the terms, while the other merely toils upon it. In modern Tanzania, this ancient wisdom exposes the grand myth of the “benefactor,” the figure like Abdul who is paraded as a successful businessman. He is not a creator of wealth nor a pioneer of industry. He is a patronage parasite, a crony whose empire is built not on innovation and competition, but on exclusive access to state power. His wealth is not earned; it is extracted, and in the process, he suffocates the genuine economic freedom of millions.

1. The Illusion of the Entrepreneur

The figure of the crony is a carefully constructed illusion. He is presented as a titan of industry, a proof that the system works, a benefactor providing jobs and development. But scratch the surface, and the reality is utterly different.

A genuine entrepreneur succeeds by creating something new or offering a better service in a competitive market. They risk their own capital. Their success depends on pleasing consumers. The crony’s path is the opposite. His success is entirely dependent on pleasing a politician. His “business model” is not innovation, but infiltration. He secures exclusive contracts, lucrative licences, and state-sponsored monopolies not because he is the most efficient or offers the best price, but because he is politically connected. He is given the keys to the national treasury and allowed to loot it, with a portion kicked back to his patrons in power. This isn’t commerce; it is a covert form of state-sponsored theft.

2. The Extraction Economy and The Death of Real Enterprise

The wealth of figures like Abdul is not created; it is diverted. It is extracted from the productive economy and funnelled into the pockets of a select few.

Stifling Competition: When a crony is granted a monopoly on, say, sugar imports or cement production, he doesn’t have to compete. He can set extortionate prices, offer shoddy quality, and crush any smaller, local competitor who dares to challenge him. This kills innovation and traps consumers in a cycle of high prices and low quality.

Corrupting Incentives: This system teaches a devastating lesson to the youth and actual entrepreneurs: success does not come from hard work, brilliant ideas, or serving your community. It comes from cultivating political connections. It redirects talent and ambition from productive endeavour to parasitic scheming.

Siphoning Public Wealth: The massive infrastructure contracts handed to these cronies are invariably inflated. The road that should cost a billion shillings costs ten billion. The difference is split between the crony and the officials who approved the deal. The public pays ten times over—first through taxes, and then again through debt and poor services.

3. The Betrayal of Ujamaa and Self-Reliance

This crony capitalism is the absolute perversion of the Tanzanian spirit of Ujamaa and kujitegemea (self-reliance). Ujamaa was meant to be about collective economics and shared prosperity. Instead, we have a system where a handful of individuals, in cahoots with the state, feast on the collective wealth.

It is the ultimate negation of self-reliance. It tells the people: “You cannot build your own wealth. You must wait for a powerful benefactor to come and do it for you.” It creates a nation of economic supplicants, dependent on the whims of a connected elite, rather than a nation of empowered citizens building their own prosperity from the ground up.

It is the ultimate negation of self-reliance. It tells the people: “You cannot build your own wealth. You must wait for a powerful benefactor to come and do it for you.” It creates a nation of economic supplicants, dependent on the whims of a connected elite, rather than a nation of empowered citizens building their own prosperity from the ground up.Reclaiming Our Economy: From Patronage to People’s Power

The solution is not to regulate the cronies or to hope for more “ethical” ones. The entire system of state-bestowed privilege must be dismantled.

The radical alternative is to build an economy that is genuinely of, by, and for the people. This means:

Promoting Cooperative Enterprise: Actively supporting worker-owned co-operatives, community-owned farms, and credit unions. These structures ensure that wealth is generated and distributed democratically among those who create it, rather than being siphoned off by an absentee owner.

Advocating for Economic Democracy: Demanding that communities have a direct say in how local resources are used and who benefits from them. This means opposing the top-down handing of land and resources to external cronies without local consent.

Building Solidarity Networks: Creating alternative supply chains and marketplaces that bypass the crony-controlled monopolies. Supporting local producers and artisans directly, keeping wealth circulating within the community.

The adage reminds us that the farmer should not be a servant on his own land. We, the people, are the farmers of this nation. The resources, the labour, and the ingenuity are ours. We must stop doing business with those who have stolen the shamba and instead reclaim it for ourselves. True economic freedom is not the freedom for a few cronies to extract wealth; it is the freedom for every community to build its own prosperity, on its own terms, without asking for permission from any patron.

Strangling the Village to Save It: The War on Self-Reliance

There is a deep and enduring wisdom in the Swahili adage, “Kidole kimoja hakivunji chawa.” (One finger cannot crush a louse). It speaks to the fundamental power of collective action, of community. The task requires the concerted effort of many. Yet, the prevailing system of governance in Tanzania operates on the exact opposite principle. It is a sustained and deliberate attack on the very idea of community. It is a top-down edict that dismisses the innate ability of people to organise, solve their own problems, and manage their resources collectively. It insists, with paternalistic arrogance, that progress is a gift that can only be delivered by a centralised power, thereby strangling the spirit of self-reliance that has been the bedrock of African societies for millennia.

1. The Logic of Disempowerment

This attack is not a passive outcome; it is an active strategy. A community that is self-sufficient and self-governing is a community that does not need a distant, central authority. It is a threat to the very justification for that authority’s existence.

Therefore, the system must deliberately dismantle community capability. It does this by:

Usurping Local Initiative: When a village collectively decides to build a small bridge or a water catchment system, that act is a declaration of independence. The state often responds not with support, but by swooping in, taking over the project, slapping a leader’s name on it, and presenting it as a state-led achievement. This teaches people that their own efforts are insignificant and that they must wait for external saviours.

Imposing Standardised “Solutions”: Central planners in faraway offices design one-size-fits-all programmes for education, agriculture, and development, ignoring the specific knowledge, conditions, and needs of unique communities. This dismisses local expertise as primitive and replaces it with often-impractical dictates from above, which frequently fail.

Monopolising Resources: By controlling all significant funding and resources, the state makes communities beggars at its door. A village cannot access funds for a self-designed project without going through countless layers of bureaucracy, where the project is often distorted to fit central priorities or denied outright if it doesn’t serve a political need.

2. The Cultural and Spiritual Damage

This assault is more than political; it is cultural and spiritual. It is a war on ways of knowing and being that long predate the modern nation-state.

Concepts like Ujamaa (familyhood) and the practice of ujima (collective work and responsibility) are rendered hollow. They are stripped of their real meaning—horizontal mutual aid—and are repurposed as slogans for top-down state control. The system teaches learned helplessness, convincing people that they are incapable of managing their own affairs. It destroys the confidence that comes from solving problems together, from the pride of building something as a community without a master orchestrating the process.

3. The Fiction of the Benevolent Centre

The entire system is propped up by a grand fiction: that centralised power is the sole engine of progress and order. This is a lie.

The reality is that centralised power, disconnected from local reality, is inherently inefficient, unaccountable, and often corrupt. It creates dependency, not development. It creates bottlenecks, not progress. The genuine, sustainable progress—the kind that lasts—has always emerged from communities themselves, from their intimate understanding of their own needs and their innate capacity to cooperate and innovate.

Reclaiming Our Communal Power: The Second Finger

The radical response to this attack is a conscious and determined revival of community power. It is the second finger coming to aid the first to crush the louse.

It is about ignoring the central planner and building the world we need ourselves. This means:

Reviving and Modernising Traditional Cooperation: Applying the spirit of ujima to modern challenges. forming community-owned energy co-operatives (like solar micro-grids), creating neighbourhood assemblies to decide on local issues, and establishing community seed banks to ensure agricultural resilience.

Creating Parallel Systems: Building networks of mutual aid that operate outside state control—whether it’s community health worker programmes, skill-sharing networks, or alternative dispute resolution circles that bypass corrupt and biased courts.

Direct Action and Occupation: Physically taking control of local resources that are being mismanaged or stolen by cronies—a water source, a forest, a piece of land—and managing them collectively for the common good.

The goal is to make the central state increasingly irrelevant to daily life. It is to prove that communities are not helpless children waiting for instructions, but are the true architects of their own destiny. We must build a society where progress is measured not by the number of projects a leader puts their name on, but by the strength, freedom, and self-reliance of its communities. For a nation built from the vibrant, confident cooperation of its villages and neighbourhoods is ungovernable by tyrants and uninteresting to parasites. It is, simply, free.

The Theft of Our Story: How They Write Themselves into History

There is a powerful Swahili adage that speaks to the essence of identity and resistance: “Mwenye kuhisi kuumia na mwenye kuumia ni watu wawili tofauti.” (He who feels the pain and he who is in pain are two different people). It draws a stark line between the lived experience of a people and the outside narrative imposed upon them. In Tanzania today, a grand and insidious theft is underway. It is not just the theft of our taxes or our resources, but the theft of our very story. By systematically slapping a leader’s name on every road, school, and power grid, the state is not celebrating development; it is seizing control of the narrative of Tanzania’s progress. It is writing a national story where the people are reduced to passive, grateful spectators, and the leader is installed as the sole protagonist, the great architect of all that is good.

1. The Architecture of a False History

This act is a form of historical engineering. It is the deliberate construction of a myth in real time. Every sign that reads “Samia’s Road” or “Samia’s Electricity” is not a mere label; it is a paragraph in a history book being written for future generations.

This narrative does not record the farmers whose taxes paid for the tarmac. It erases the engineers who designed the grid and the labourers who poured the concrete under the blazing sun. It airbrushes out the struggles of communities who demanded these services for decades. In their place, it inserts a single hero. This creates a distorted reality where development is an act of individual will bestow from above, rather than the culmination of collective struggle and investment from below. It is a lie designed to make the people forget their own power, their own labour, and their own role in shaping their world.

2. The Psychological Impact: Manufacturing Passivity

A people who are written out of their own history become mentally disempowered. If every achievement is attributed to a single leader, the subconscious lesson is that you, as an individual and as a community, are incapable of achieving great things on your own.

This narrative kills ambition and initiative. Why should a community organise to build its own clinic if the story of success is always about waiting for a saviour from Dodoma? It fosters a culture of passivity and dependency, where people look to the state for direction and deliverance rather than looking to each other for cooperation and mutual aid. It is a psychological cage, more effective than any prison, because the inmates guard it themselves.

3. The Political Purpose: Justifying Absolute Power

This control of narrative is the ultimate tool for legitimising and entrenching power. If the leader is the sole source of progress, then questioning the leader is tantamount to opposing progress itself. Dissent can be framed not as a civic right, but as a form of national sabotage.

This manufactured story justifies the concentration of power. It argues that for development to continue, the great architect must be protected, obeyed, and freed from petty accountability. It creates a political culture where criticism is seen as disloyalty, and blind obedience is the highest form of patriotism. It is the story a king writes to justify his crown.

Reclaiming Our Story: The Radical Act of Truth-Telling

The most profound resistance to this theft is to seize back the pen and write our own story. It is a radical act of truth-telling that begins with language.

We must consciously, deliberately, and publicly correct the record. We must never say “Samia’s road.” We must say, “the road we built with our taxes.” We must say, “the school our community fought for.”

This is more than semantics; it is an act of intellectual self-defence. It is the second part of the adage: insisting that the one who feels the pain must be the one who tells the story. We must become the authors of our own history.

This means:

Creating Our Own Media: Supporting and producing independent blogs, community radio, and social media channels that document stories from the ground up—highlighting community initiatives, worker struggles, and the true cost of state-led “development.”

Practising Oral History: In our families and communities, consciously telling the true stories of how things were built, who really paid the price, and who truly deserves the credit, ensuring the official lie does not become the accepted truth for the next generation.

Celebrating Collective Achievement: Organising events and creating art that honours the workers, the engineers, the farmers, and the activists—the real protagonists of our national story.

By reclaiming our narrative, we do more than just expose a lie; we rediscover our own agency. We remember that history is not made by great men and women, but by the countless, nameless actions of ordinary people cooperating, striving, and building together. A future written by everyone, for everyone, is a future that no single ruler can ever own or control.

The Great Conflation: How They Merge Leader and Nation to Silence Dissent

There is a profound Swahili adage that serves as a warning against such dangerous unity: “Maji usiyoyafika ndio yaliyo na uweza wa kukufisha.” (It is the water you have not yet reached that has the power to kill you). The meaning is clear: the greatest dangers are those that are not yet fully visible or understood. In Tanzania today, a most perilous conflation is taking place, one that drowns out dissent and critical thought. The state, its institutions, and the individual leader are being deliberately merged into a single, indistinguishable entity.

This blurring of lines is a masterful political trick, designed to ensure that any criticism of a government policy, any demand for accountability, is instantly twisted into a personal attack on the leader, and by extension, framed as an attack on the nation itself. This is the ultimate silencing mechanism, and it is killing the possibility of healthy debate.

This blurring of lines is a masterful political trick, designed to ensure that any criticism of a government policy, any demand for accountability, is instantly twisted into a personal attack on the leader, and by extension, framed as an attack on the nation itself. This is the ultimate silencing mechanism, and it is killing the possibility of healthy debate.1. The Mechanics of the Merger

This is not an organic process; it is a calculated strategy executed through propaganda, language, and symbolism.

The Language of Ownership: The constant repetition of phrases like “Samia’s Police,” “Samia’s Schools,” and “Samia’s Development” is not accidental. It is a linguistic sleight of hand that transfers ownership of the nation’s institutions from the public to the person. The police are no longer a public service; they are her personal property. The schools are not our community projects; they are her charitable donations.

The Symbolic Fusion: The leader’s image is everywhere, superimposed on national projects. The national flag and the leader’s persona become intertwined in official media. This visual propaganda creates a subconscious link in the public mind: to love Tanzania is to love the leader; to question the leader is to betray Tanzania.

2. The Stifling of Debate and the Death of Accountability

This conflation has a devastating effect on civic discourse and governance.

Criticism Becomes Treason: A citizen complaining about the poor state of a “Samia’s Road” is no longer just a taxpayer pointing out shoddy workmanship. In the new, blurred reality, they are insulting a personal gift from the leader. Their legitimate grievance is rebranded as personal ingratitude and disloyalty to the nation.

Policy is Above Scrutiny: How can you debate the economic sense of a mega-project when it is presented not as a policy choice but as a pet project of the leader? Opposition is framed not as a difference of opinion but as a character assassination. This makes rational, evidence-based policy discussion impossible.

Accountability Evaporates: When the leader and the state are one, holding the government accountable for failure—be it corruption, economic mismanagement, or human rights abuses—becomes an impossible task. To demand answers is to insult the nation’s figurehead. The system becomes immune to feedback, doomed to repeat its mistakes and amplify its failures.

3. The Betrayal of True Patriotism

This strategy is the deepest betrayal of genuine patriotism. True love for one’s country involves a passionate desire to see it better, to correct its course when it strays, and to hold its stewards to the highest standard. A patriot asks difficult questions.

The blurred-line doctrine perverts this. It defines patriotism as unquestioning loyalty to the current ruler. It replaces critical love with sycophantic obedience. It creates a nation of cheerleaders, when what we desperately need is a nation of critical thinkers and engaged citizens.

The blurred-line doctrine perverts this. It defines patriotism as unquestioning loyalty to the current ruler. It replaces critical love with sycophantic obedience. It creates a nation of cheerleaders, when what we desperately need is a nation of critical thinkers and engaged citizens.Reclaiming the Distinction: The Radical Act of Separation

The resistance to this conflation is a radical act of clarity. It involves surgically separating the concepts that the power structure has so deliberately fused.

We must constantly, forcefully, and publicly reaffirm the truth:

The Leader is not the State. The state is the collection of institutions meant to serve us, the people. It is ours.

The Leader is not the Nation. The nation is the land, the culture, the history, and the people. It is a living entity that existed long before the current ruler and will exist long after.

This means changing our language. It is not “Samia’s policy”; it is “the government’s policy,” and we have every right to critique it. It is not “an attack on Samia”; it is “a demand for accountability from our public servants.”

We must revive the true meaning of patriotism: the courage to criticise, the duty to demand better, and the unwavering belief that our nation deserves more than the cult of a single individual. The water we must now reach for is the clear, clean water of truth: the truth that the nation belongs to its people, and its leaders are merely temporary hires—employees who must be constantly audited and who can be fired if they fail in their duties to the true owners: us.

The Vampire Economy: How Our Lifeblood is Drained for a Few

There is a stark Swahili adage that captures the essence of this plunder: “Mkulima akipata ujana, shamba linapata utosi.” (When the farmer gets youth, the farm gets baldness). It speaks to a devastating imbalance where the vitality of one is consumed to create barrenness for the many. The eye-watering sums revealed in the leaked finances of the IGP and his ilk are not evidence of a thriving economy. They are the spoils of a vampire economy, a system designed not to create wealth but to extract it. This is not value creation; it is value diversion on a grand scale—a systematic siphoning of the lifeblood of the Tanzanian people into the offshore accounts and luxurious lifestyles of a tiny, parasitic elite.

1. The Mechanics of Theft: From Public Good to Private Gain

The process is a sophisticated form of economic violence, disguised as governance and business.

Inflation and Theft: The massive, illicit wealth of officials is not manufactured from thin air. It is our money. It is the difference between the real cost of a road and the inflated price tag on the contract awarded to a crony like Abdul. It is the taxes collected from market traders and street vendors that are diverted into private pockets instead of being spent on public services. Every billion shilling stolen from a public project is a hospital ward not built, a classroom without textbooks, a village without clean water.

The Illusion of Wealth Creation: Figures like Abdul are falsely held up as “job creators” and “investors.” This is a lie. A true investor risks their own capital to build something new. A parasite uses political connections to secure a monopoly or a sweetheart deal, then uses that privileged position to extract maximum profit with minimum effort, stifling genuine competition and innovation. Their wealth is a sign of economic sickness, not health. It is a tumour, not a muscle.

2. The Human Cost: The Many Fund the Luxury of the Few

The extraction is not a victimless crime. It has a direct, measurable, and brutal human cost.

The youth whose future is stolen to build the palaces of the powerful are the true cost. The farmer who cannot get a fair price because the market is controlled by a cartel pays for it. The mother who pays over the odds for medicine because of corrupt procurement deals pays for it. The entire nation is forced into a state of perpetual austerity so that a select few can live in obscene luxury. This is not a free market; it is a rigged system, where the wealth produced by the labour of the many is systematically diverted to the idle few.

3. The Systemic Lie: Hiding the Theft

The system then compounds the theft by lying about it. It labels this extraction “foreign direct investment” or “economic growth.” It points to the gleaming skyscrapers and shopping malls owned by the cronies as symbols of national progress, while ignoring the fact that they were built with stolen funds and serve only the richest fraction of society.

This narrative hides the baldness of the farm while celebrating the youth of the parasite. It is a grand illusion designed to make us accept our poverty as inevitable and their wealth as deserved.

Reclaiming Our Wealth: From Extraction to Circulation

The solution is not to tinker with the extractive system or to beg for a fairer share of the spoils. The entire vampire logic must be rejected and replaced.

The radical alternative is to build an economy based on circulation, not extraction. This means:

Building Community Wealth: Actively supporting and creating worker cooperatives, community-owned farms, and credit unions. These structures ensure that wealth generated by a community is reinvested in that community, rather than being extracted by absentee owners and shareholders.

Direct Action and Reclamation: Physically resisting the theft of land and resources. Occupying idle land held by speculators and putting it to community use. Establishing people’s audits to track public funds and demand their return.

Localising Economies: Prioritising trade and exchange within and between communities to create resilient, self-sufficient networks that are less vulnerable to national-level corruption and global exploitation.

We must see the leaked bank statements for what they are: evidence of a crime against the people. Our goal must be to dismantle the entire machinery of extraction and build an economy where, like the adage reversed, the vitality of the farmer directly nourishes the land for all. Where wealth is measured by the well-being of the many, not by the yachts of the few. An economy that serves the people, not preys upon them.

The Poisoned Well: When Betrayal Kills the Spirit of Togetherness

There is a deeply resonant Swahili adage that speaks to the heart of this crisis: “Ukucha ukaucha, ukingojea mwenyewe hana haja nawe.” (You mature and mature, only to find that the one you waited for has no need for you). It captures the profound betrayal of invested hope. In Tanzania, the systemic corruption and the weaponisation of public institutions have done more than just rob the treasury; they have poisoned the nation’s well of trust. This erosion is catastrophic because it targets not just faith in a bad government, but faith in the very principle of collective action itself. It risks teaching a generation a devastating lie: that all organisation is inherently corrupt, that working together is futile, and that the only rational response is to retreat into isolated, selfish survival. This is the final victory of the corrupt—to make their cynical worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy by destroying our belief in each other.

1. The Betrayal of the Social Contract

Trust is the invisible foundation upon which any society is built. We agree to collective rules and contribute to collective projects—like paying taxes or following laws—based on a shared understanding that others, especially those in authority, will do the same.

When that trust is shattered—when the IGP is revealed to be a billionaire crook, when our taxes are stolen to build palaces in Masaki, when every public project is branded as a personal gift—the social contract is not just broken; it is revealed to have been a sham. People feel like fools for having ever believed in it. This breeds a deep, corrosive cynicism that extends far beyond the government. It leads people to ask: “If those at the top are only in it for themselves, why shouldn’t I be?”

2. The Attack on Horizontal Organising

This is the most insidious damage. The erosion of trust doesn’t just make people hate vertical power (the government); it makes them suspicious of horizontal power—the power of community, of cooperation, of mutual aid.

If every large organisation people encounter—the state, the big corporations in bed with it—is corrupt, the natural conclusion is that all organisation leads to corruption. This makes it incredibly difficult to build the very thing that could replace the rotten system: genuine, grassroots communities of solidarity. People become reluctant to pool money for a community project, fearing the treasurer will embezzle it. They hesitate to join a cooperative, suspecting the leaders will become just like the politicians. The corrupt system, through its own example, actively discourages the creation of ethical alternatives.

3. The Culture of Cynical Isolation